Life in the USA is not normal. It feels pointless and trivial to be talking about small looks at the fascinating natural world when the country is being dismantled. But these posts will continue, as a statement of resistance. I hope you continue to enjoy and learn from them. Stand Up For Science!

The United Nations has named 2025 the International Year of Glaciers' Preservation, and March 21 was the first ever World Day for Glaciers, in partnership with UNESCO and the World Meteorological Organization.

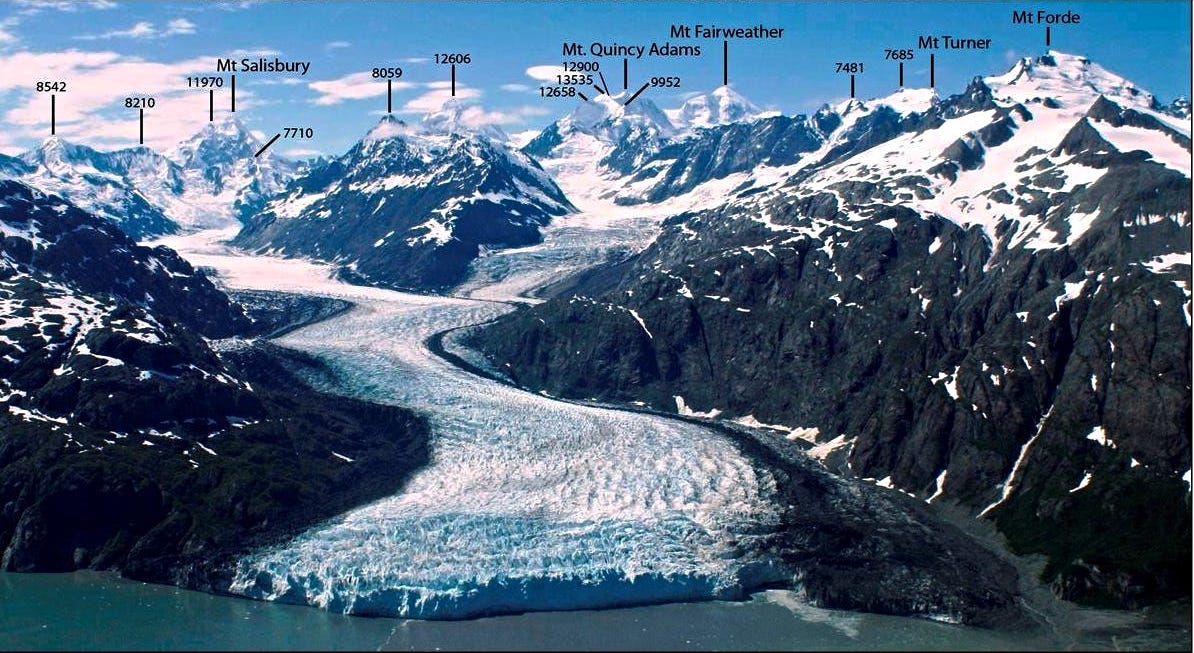

The curved surfaces in the toe of Margerie Glacier, near the head of Glacier Bay in Alaska, are probably not tectonic folds in the standard sense of squeezing or compression. Rather, they are probably a consequence of differential flow rates, with the unconstrained middle of the glacier moving faster than the edges which drag along the rocks adjacent to the ice. That creates space problems within the ice mass, which are accommodated by changing shape, resulting in the curves you see in the photo.

The ice in the second photo (above) is black with a covering of probable volcanic ash, but if you look closely you can see convoluted geometry in the ice, including what looks like a recumbent fold at the left. The differential flow can do some amazing things in ice.

The black stuff within the ice that defines the folds is rock that fell off the adjacent cliffs onto the ice at various times, combined with general dust and perhaps some volcanic ash. We’d call all that debris “moraine” or morainal material, and when the glacier melts and drops the material onto the earth’s surface, the geomorphic feature is also called a moraine, with many modifications as to position and geometry —lateral, medial, end, terminal, ground, among others. The word moraine is ultimately from a Latin word for “snout,” for the frequent (but by no means exclusive) occurrence of moraines at the “snout,” the end, of a glacier.

Margerie Glacier is about 21 miles long and until the 1990s had been flowing seaward fairly consistently at around 6 feet a day, but in the late 1990s it began to recede. Note that when a glacier “recedes,” it does not back up. It’s just that its downward flow rate is exceeded by its rate of melting.

In 1794 when Captain George Vancouver visited, all of Glacier Bay was covered with ice. By 1879 when John Muir was there, ice had retreated 77 km (48 miles) into the bay, and since then it has retreated to a total of 105 km (65 miles), so that today only Margerie near the head of the bay and several other tidewater glaciers occupy inlets around the margin of the bay.

In the image above, my photos of the toe of Margerie Glacier were from a spot in the bay just to the right of the arrowhead from the “Margerie Glacier” label. All of Glacier Bay was solid ice 225 years ago.

The ice cave you see in the top photo is mostly the result of glacial calving and sea wave action. Margerie Glacier is hanging above the sea floor – around 600 feet above it. That will certainly contribute to accelerating the glacial melting, since in many cases melting is far more active at glaciers’ bases than on the top.

My photos are from a Smithsonian Journey in 2005 where I got to serve as the house (or boat) geologist.

Margerie Glacier was named for French geologist and geographer Emmanuel Marie Pierre Martin Jacquin de Margerie (1862-1953) who visited the area in 1913.

Ironic having 'Year of Glacier Preservation' given that 2025 will be a year of ever accelerating glacier loss.