I mostly get maps for the information they contain, whether topographic, geologic, highway, political, or whatever. My obsessive tendencies emerge when I get maps I can have little or no conceivable use for, simply because they are beautiful works of cartography, PLUS cool information.

This four-foot-wide map of the island of Molokaʻi, Hawaii, published by the US Geological Survey in 1952, is one of the latter. It’s the shaded relief edition, at 1:62,500 scale, and I paid ten cents for it about 1990. It’s a pretty map, but what I really enjoy is the learning I get from the interconnected rabbit holes that start with encountering a map like this, which I had completely forgotten that I have. I just rediscovered it while sorting things.

The first rabbit hole is the geography. The map shows tiny Kalawao County along the north coast of the island. I knew it was established as a separate county for the leper colony there, but I didn’t know it is the smallest county by land area in the US (12 square miles) and second smallest by population (82 in the 2020 census, vs Loving County, Texas, at 64). The county was formed in 1905 when the Territory of Hawaii’s 5 counties were established, but now, because of the small and declining population, it does not have its own government and is administered by the Hawaii Department of Health. Otherwise for most purposes it is effectively a part of Maui County which includes the rest of Molokaʻi island and the islands of Maui, Lānaʻi, Kahoʻolawe, and Molokini. Kalawao County’s history as a quarantined leper colony from 1866 to 1969 is sad and interesting.

The geological rabbit hole might not have been that interesting; it’s well known that all the Hawaiian Islands are essentially oceanic basalts erupted in shield volcanoes, and that the chain’s volcanoes are younger the further southeast you go, because the Pacific oceanic plate is moving northwest relative to a deep mantle upwelling of heat (called a hot spot) that burps periodically to make the volcanoes. The hot spot is presently under the southeast part of the big island of Hawaiʻi, where Kīlauea is currently active, and a bit further to the southeast, where the active submarine volcano Lōʻihi has produced a seamount that stands almost 10,000 feet above the sea floor.

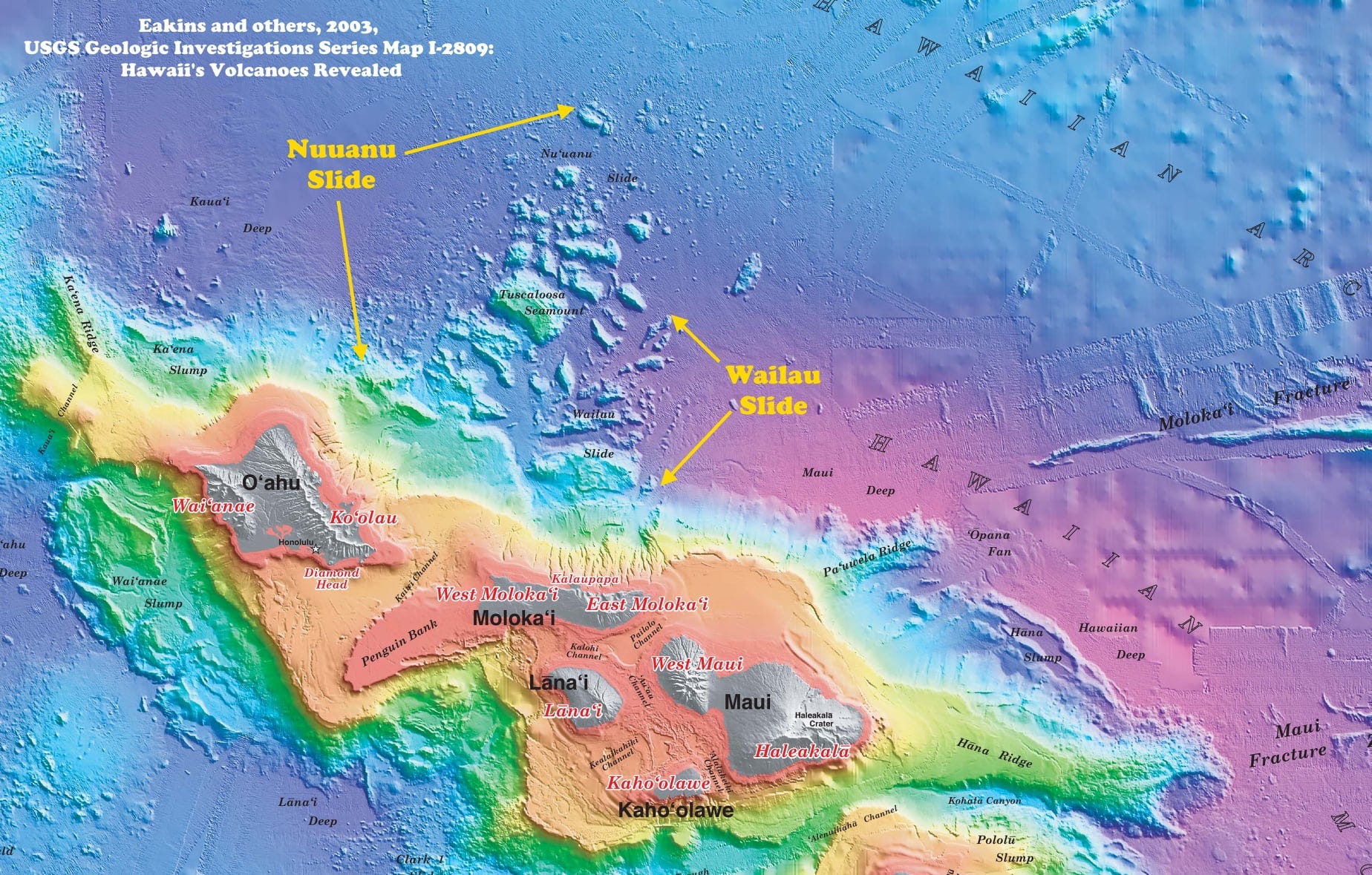

The significantly more obscure geological rabbit hole lies in the nearly straight east-west northern coast of Molokaʻi. It is interrupted by the Kalaupapa (or Makanalua) Peninsula (where the leper colony was located), centered on the Kauhakō Crater, formed about 230,000 to 300,000 years ago by the eruption of Pu'u' 'Uao volcano, the youngest on Molokaʻi. Most of the island was formed by eruptions of East and West Molokaʻi volcanoes about 2,000,000 to 1,300,000 years ago. East and West Molokaʻi were formerly connected to the volcanoes that comprise Maui, Lānaʻi, and Kahoʻolawe, making for a composite island that was probably larger than today’s big island of Hawaiʻi. The color bathymetric map above is from Eakins and others, 2003, USGS Geologic Investigations Series Map I-2809: Hawaii's Volcanoes Revealed.

After (or in the last stages of) the eruptions of East and West Molokaʻi volcanoes, but before the eruption of Pu'u' 'Uao to form the Kalaupapa Peninsula, dramatic events happened to form the straight east-west edge of northern Molokaʻi. About 1.3 to 1.4 million years ago, the northern third of Molokaʻi, the northern flank of the volcanoes, collapsed into the sea. The present-day cliffs on the northern coast of Molokaʻi, which rise about 900 m (3,000 ft) from the sea (making them some of the highest coastal cliffs in the world) are the remnant expression of that collapse (enhanced by further coastal erosion), although the cliff face is not likely to explicitly be the headwall of the landslide that resulted from the collapse (Clague & Moore, 2002, The proximal part of the giant submarine Wailau landslide, Molokai, Hawaii: Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research, Volume 113, Issues 1–2, pages 259-287).

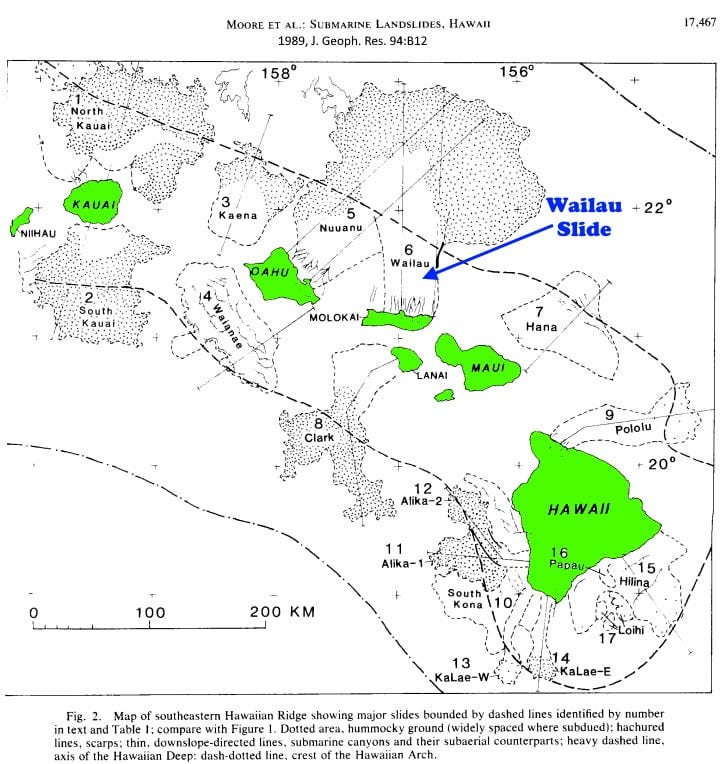

The collapsed part of the volcano created the huge Wailau submarine landslide whose remnants are visible in sonar and other imagery on the sea floor north of Molokaʻi. Such submarine slides are abundant, almost ubiquitous, off the flanks of the Hawaiian Islands. The largest, Nuuanu, created the nearly straight NW-SE coastline of Oahu. It covers about 23,000 square kilometers (8,900 square miles, about the size of Beaverhead and Madison Counties, Montana, combined, or the state of New Hampshire). The Wailau slide off Molokaʻi overrode part of the older Nuuanu slide; Wailau is the second or third largest of the Hawaiian submarine slides, at about 13,000 sq km (Moore and others, 1989, Prodigious submarine landslides on the Hawaiian ridge: J. Geoph. Res. 94:B12, p. 17,465-17,484; a figure from that paper is shared above as well).

When the Wailau landslide occurred about 1.4 million years ago, it generated a tsunami modeled at a height of about 65 meters (210 feet) on Molokaʻi itself and probably around 30 to 40 meters (100-140 feet) when it reached coastal Alaska, Canada, and Washington (Satake and others, 2002, Three‐Dimensional Reconstruction and Tsunami Model of the Nuuanu and Wailau Giant Landslides, Hawaii: American Geophys. Union Geophysical Monograph 128, p. 333).

Armchair exploration has its charms. Down the rabbit hole everytime. Also have some "useless" old maps, useless until I need to find certain information, often a name or small detail, that does not appear on readily available modern mapping.

Absolutely fascinating! My wife is from Kailua, Oahu and knew alot of this, she remarked those geologic processes are still going on. A very dynamic environment. I hadn't heard (nor had she) about that southeastern seamount, now 10,000 feet off the ocean floor. I wonder how long before it forms a new Hawaiian island?