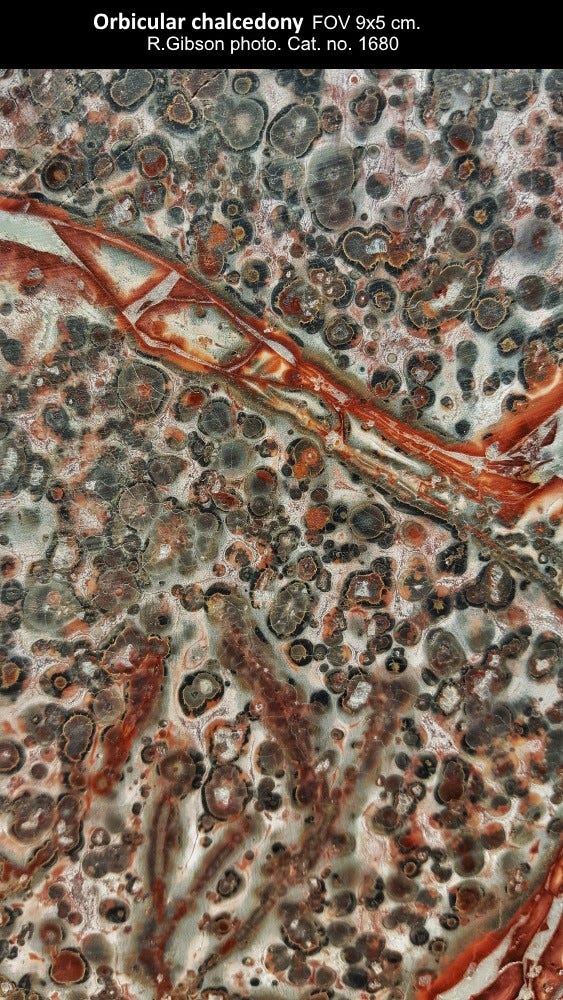

Orbicular chalcedony

Or make up some other name if you wish

Chalcedony is the general term for micro- or cryptocrystalline quartz, silicon dioxide. Its dozens of varietal names come from colors and patterns caused by alternating inclusions of various materials. Red and other colors of chalcedony, often the result of inclusions of iron oxide, is usually called jasper. Some might call some of this rock a variety of agate, which usually means chalcedony with some kind of banding, but jasper usually lacks such banding and transparency, and I personally would not equate jasper and agate.

I’d call this rock “orbicular chalcedony,” although there’s enough red to maybe call it orbicular jasper. “Jasper” is often used pretty broadly and can include shades of green, orange, yellow, pink, purple, black, and brown, all caused by varying amounts of iron in its various oxidation states, plus or minus other stuff. Iron is by far the most common coloring agent in rocks.

Although it’s pretty and every piece is unique, there are enough occurrences around the world that I don’t know where this was from, but Madagascar is a fair guess. In the lapidary trade, material like this from Madagascar is sometimes called “ocean jasper.” The plethora of marketing names for similar material, in addition to “ocean jasper,” includes elarite, nebula stone, and Kambala jasper, all of which are made up and do not have real mineralogical meaning.

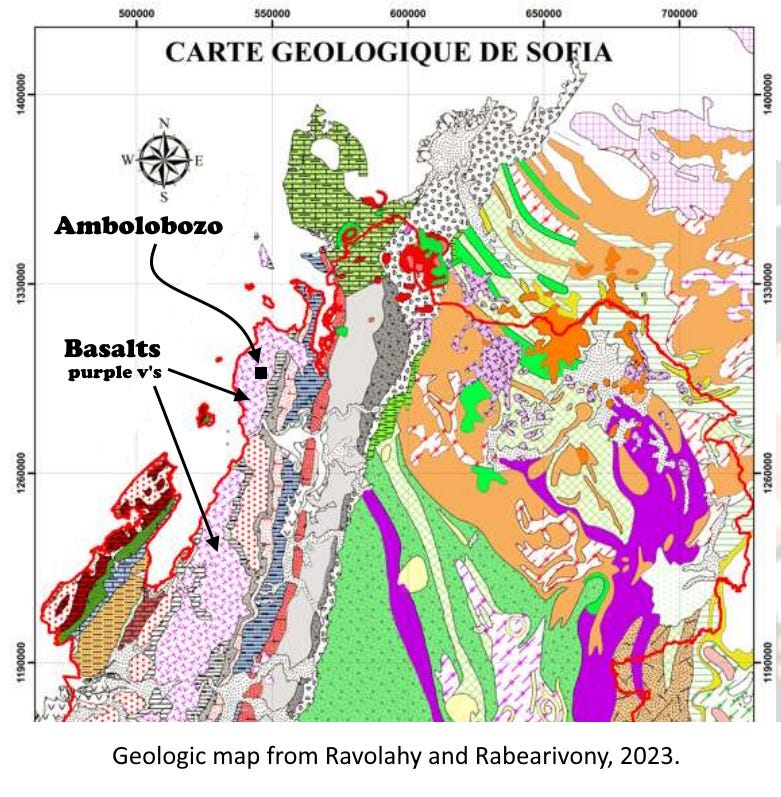

My father had this cut, unpolished slab for working into lapidary creations like belt buckles. He had this when he died in 1996, so it is probably from some location other than the famous Madagascar ocean jasper locality at Marovato near Ambolobozo on the northwest coast, which by most accounts was discovered in 2000.

Although “ocean jasper” is usually said to come from nodules in silicified rhyolites or volcanic ash deposits (tuff), the area of Ambolobozo is mapped as basaltic (Ravolahy and Rabearivony, 2023, Genetic classification of mineral deposits and mineral substances in the Sofia region: International Journal of Advance Research and Innovative Ideas in Education (IJARIIE), v. 9, issue 6), and those authors indicate that the Ambolobozo decorative and ornamental stone comes from basaltic rocks.

The chalcedony may have formed in vugs or other cavities within the basalt. Madagascar mineral miners are also notorious for not giving exact locations for mineral finds, so it’s possible that the real source is in rhyolite or ash somewhere else in the region, or the rhyolitic rocks may be of small extent and not shown on the maps I’ve seen.

The basalt and other volcanic rocks are related to the breakup and rifting of Madagascar away from what is now the Kenya-Somali coast of East Africa. Age dates are few, but the basalt and rifting are Cretaceous (Cucciniello and others, 2015, The Madagascar Large Igneous Province: Large Igneous Provinces Commission, Int’l. Assoc. of Volcanology & Chem. of the Earth’s Interior).

The orbicular shapes may form when nuclei develop in a solidifying silica gel in a void space in the rock, attracting various molecules to those central points and resulting in the spheres and ovoids you see here in cross-section. An alternative is some kind of silicification by mineral-rich waters percolating through porous material (the rhyolite or tuff?) in the solid state. Microscopically, the material is clearly chalcedony, with radial and fibrous habits producing the spherules (Tremblay and Cesare, 2014, A closer look at ocean jasper: Elements 10 (5): 398)

The big cracks across the upper part and lower right are slightly later fractures, filled with more iron-oxide-rich silica along the cracks and around the pieces of older rock within the cracks. The black colors of most of the spherules might come from unoxidized iron and/or manganese. Without analysis or at least a thin section, it’s not certain that my specimen is really chalcedony; it may more likely be “spherulitic rhyolite” such as some of the examples here. Similar material called “rainforest jasper” occurs in northern Queensland, Australia, as pointed out to me by reader John Hoffman (Thanks!).

That's ok. I chalk everything black up to Fe/Mn. In all the reading I've done, there's not been other suggestions, except maybe bitumen of some grade. But I don't think that's black when it gets thin, stain-like. Thanks for answering.

Richard, do you know what the other chemical compounds might be that you mention in the last sentence.; do you have a few examples?