The three tiny Chincha Islands lie 21 km (13 mi) off Peru’s southwest coast near Pisco. Covering barely three square kilometers (a little more than one square mile), and rising only 34 meters (113 feet) above the sea, the islets are home to sea lions and hundreds of sea birds. Like many ocean islands, such locales became avian refuges; few predators meant birds could nest in relative security.

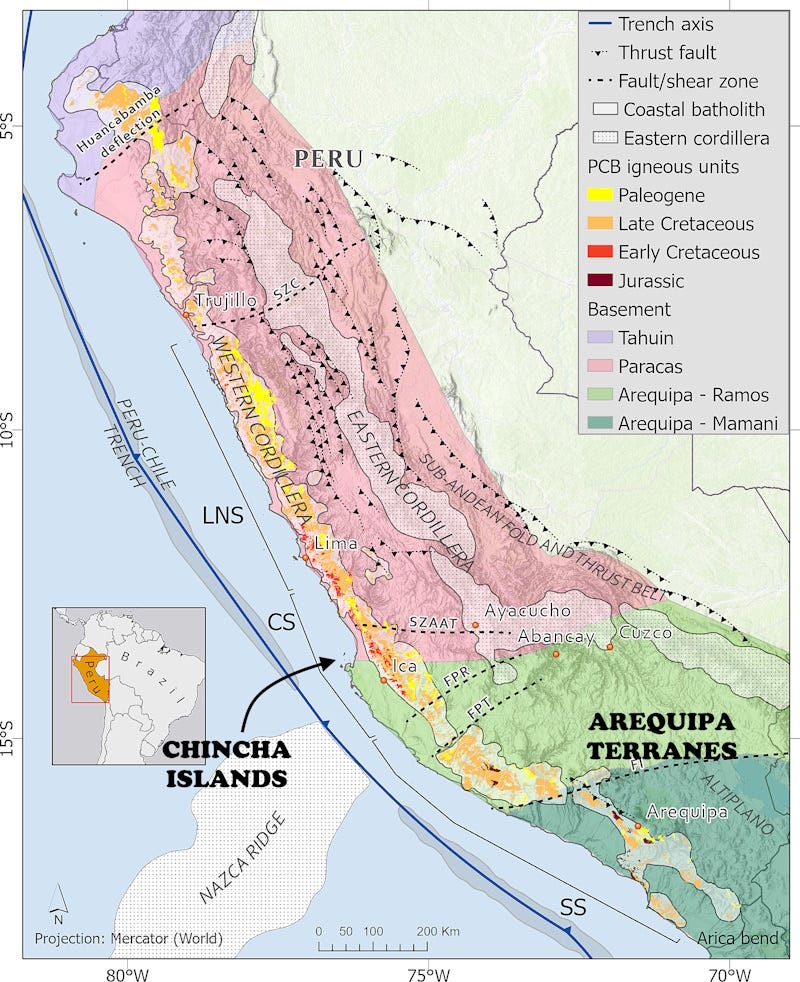

Granite underpins these islands, near the northwestern end of an ancient elongate continental block called the Arequipa Massif (in two shades of green in the map above). It formed during Paleoproterozoic time (roughly 1.8 billion years ago) and amalgamated with the ancestral core of the South American continent about one billion years ago, part of the assembly of an early supercontinent named Rodinia. That continent broke apart around 600-800 million years ago, leaving the Arequipa Massif near the edge of what would become South America. Granitic intrusions forced their way into these rocks about 470 million years ago (Ordovician). All that preceded the modern Andes; they rose through relatively simple and relatively recent subduction pushing oceanic crust beneath the South American craton, ultimately changing the flow direction of the Amazon. Faulting, continuing today, shifts the rocks of the Arequipa Massif, and contributed to the formation of the Chincha Islands.

Of all that complex history, the most important economic aspect is the simple fact that they are islands. Few islands are found on the west coast of South America between Ecuador and central Chile, a coastline of 4,000 km (2,500 miles). Islands provide a haven from predators for birds: albatrosses, guillemots, cormorants, penguins and more nest and rest on the Chincha Islands and have done so for thousands of years—long enough for thick piles of guano to build up atop the granite. In some places, seven meters or more (22 feet, as much as a fifth of the islands’ elevation) is guano.

Quechua-speaking Incas called sea-bird excrement wanu, a word that became guano in Spanish and entered the English language unchanged by 1604. Incas used it to enhance agricultural soils, but it was not until 1802 when Alexander von Humboldt wrote of its use as fertilizer that the rich deposits along the west coast of South America attracted the attention of Europeans. Nitrate-rich Peruvian guano began to be exported as fertilizer about 1840. And the saltpeter (sodium nitrate) content’s potential for making gunpowder was lost on no one.

Unscrupulous management included mining by Chinese slaves in the 1850s, resulting in at least 60 Chinese suicides from 1852 to 1854. Refugees from the Taiping Rebellion (1850-1864) in China sought lives anywhere else; many came to the United States to seek fortunes in California’s gold fields. Those who went to work the guano mines on the Chincha Islands likely regretted the decision, if it was voluntary. Of a thousand Easter Islanders taken as slaves to work the guano mines in 1862, only 100 survived.

The guano war, known as the Chincha Islands War, the Spanish-Peruvian War, and other names, occurred as Spain attempted to reassert influence on its former colonies including Peru. Spain had not recognized Peru’s independence in 1821 and did not do so until 1879. On April 14, 1864, a Spanish fleet captured the Chinchas, whose guano provided at least 60% of Peru’s revenues at the time. Chile, Bolivia, and Ecuador joined Peru as allies in 1865 and 1866. After the battle of Callao on May 2, 1866, in which both sides claimed victory, the Spanish fleet withdrew, and the South American countries were effectively the victors in the war. Guano from the Chincha Islands was a pawn in a war fought primarily, it seems, for political or economic prestige.

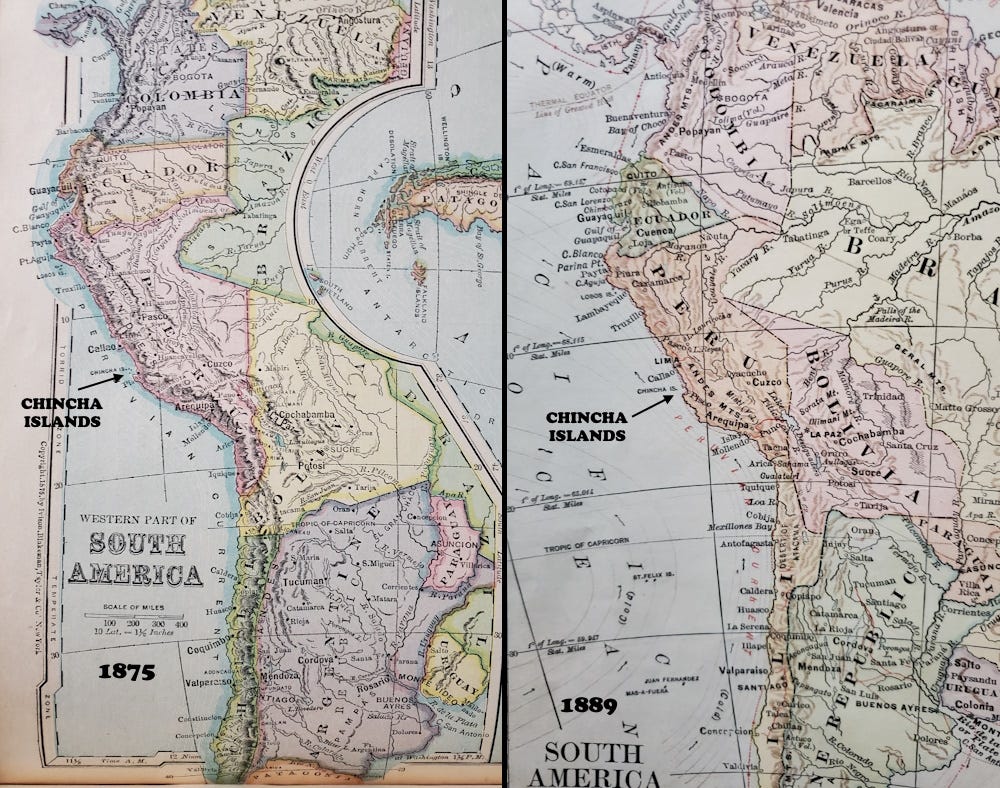

Peru’s guano industry, based in the Chincha Islands, was losing steam by the mid-1870s as extensive mineral nitrate deposits on the mainland began to be exploited. Disputes over control of those nitrates led to a second regional conflict.

The War of the Pacific, in 1879-84, pitted neighbor against neighbor in a struggle for economic resources. Also known as the Saltpeter War, it changed the map of South America and impacted national economies to the present day.

In 1879 Peru’s territory extended to about 22°S latitude, into what is now northernmost Chile. From 22° to 24°S, the coast including the city of Antofagasta was part of Bolivia; Chile lay south of 24°S. The region in question is the Atacama Desert, nearly the driest land on earth. But the area held rich nitrate deposits and a small mining area known as Chuquicamata. In 1879 nitrates were far more valuable than Chuquicamata’s copper, and all three adjacent South American nations coveted those rich nitrate deposits. Bolivia’s attempt to tax nitrate miners (many of them Chilean) and the nitrate-hauling railroad was the casus belli that touched off the war.

Five years of largely guerilla fighting between Chile and a Peru-Bolivia alliance ended in a truce in 1884 and de facto new boundaries, but a formal peace treaty was not signed until 1904 when national boundary lines were formalized. Chile ended up with all of the disputed territory (Argentina also gained part of southern Bolivia), and Bolivia became a landlocked nation. To this day each Bolivian government has had as official policy the goal of regaining the coastal Department of Litoral, which had been part of Bolivia for 50 years.

Today, nitrogenous fertilizer (ammonia) is produced from natural gas and directly from atmospheric nitrogen. Although U.S. plants produce enough to put it in a three-way tie for second-largest producer in the world (with India, Russia, and the U.S. at 9% each, after China’s dominant 29% of world production), in 2010, U.S. imports still amounted to 40% of its needs, and came from Trinidad and Tobago, 55%; Canada, 14%; Russia, 14%; and Ukraine, 10%. In 2023, because of increased U.S. production and the Russia-Ukraine war, U.S. import dependency is down to 6%, and almost all those imports come from Trinidad & Tobago and Canada. Exports of ammonia and nitrogenous fertilizers account for nearly a third of the value of Trinidad & Tobago’s exports.

Peru and Chile are no longer significant players in the world of nitrate fertilizers because the Haber-Bosch process to synthetically produce ammonia from atmospheric nitrogen came to dominate the industry after 1913, but Peru maintains a flourishing niche industry mining specialty guanos for organic fertilizer. Today’s guano miners take home about $425 a month, more than double the Peruvian minimum wage.

Sodium and potassium nitrate minerals such as those in the guano of the Chincha Islands and Atacama Desert play a trivial role in today’s nitrogen/ammonia market, and the minerals are usually unattractive except to systematic mineral collectors, who aspire to one of everything. I don’t have anything from the Chincha Islands, and if you weren’t too impressed with my photos of halloysite, you probably won’t care much for the pictures above of ammonium and nitrate minerals in my collection (and I won’t blame you). These examples of niter, KNO3, letovichite, (NH4)3H(SO4)2, and boussingaultite, (NH4)2Mg(SO4)2 · 6H2O, are little more than white efflorescences of soft, feathery to powdery material.

Some non-nitrate minerals from the Atacama Desert are indeed quite pretty, like the amarantite above. It’s iron sulfate, Fe3+2(SO4)2O · 7H2O.

If you’re read this far, you might also be interested in the ammonia-bearing minerals hannayite and struvite, which occur in human urinary stones.

The Chincha Islands were noteworthy enough to make an appearance in Mark Twain’s Roughing It, published in 1872 and dedicated to Twain’s friend from his mining days in Nevada, Calvin H. Higbie. Twain described one Captain Ned Blakely in Chapter 50:

He sailed for the Chincha Islands in command of a guano ship. … It was Capt. Ned’s first voyage to the Chinchas, but his fame had gone before him—the fame of being a man who would fight at the dropping of a handkerchief, when imposed upon, and would stand no nonsense. It was a fame well earned. Arrived in the islands, he found that the staple of conversation was the exploits of one Bill Noakes, a bully, the mate of a trading ship. This man had created a small reign of terror there. …

Chincha comes from the name of the indigenous people who lived along the coast of what is now Peru in pre-Hispanic time. In the Chincha Quechua language, their name for themselves meant “ocelot,” the native spotted wildcat Leopardus pardalis. The Chincha believed themselves to be descended from ocelots and worshiped an ocelot god.

This post was modified, expanded, and updated from text in my 2011 book, What Things Are Made Of.

Fascinating.

Last year I wrote a story about Huamancantac, who was (or is) the Inca god in charge of guano. Regret to say that not having access to geological maps my fictional guano island was of rhyolite rather than granite.