Life in the USA is not normal. It feels pointless and trivial to be talking about small looks at the fascinating natural world when the country is being dismantled. But these posts will continue, as a statement of resistance and promotion of science. I hope you continue to enjoy and learn from them.

For this 200th post, I thought I’d share some information about you readers. 859 subscribers and followers come from 40 US states (Montana, 18%; California, 13%; Colorado, 8%; Texas, 8%; Washington, 6%) and 65 countries (USA, 61%, U.K., 6%; Canada, 6%; Australia, 5%; Turkey 2%). Together with other readers, you give The Geologic Column about 9,600 views per month. I appreciate you all very much, with a special shout-out to those who have supported this effort with voluntary donations – I know who you are and I’m grateful!

The most popular posts have been

1. An unexpectedly linear magnetic anomaly 2. Antimony 3. Silver 4. Chaco Canyon 5. Asbestos 6. Spotted Rocks

If I’ve learned anything from doing this, it’s that there’s no predicting what will be popular! But that’s why I try to mix things up and offer as much diversity as I can, a sampling of the world of geology. And it’s a way for me to learn, too.

Thanks for your interest!

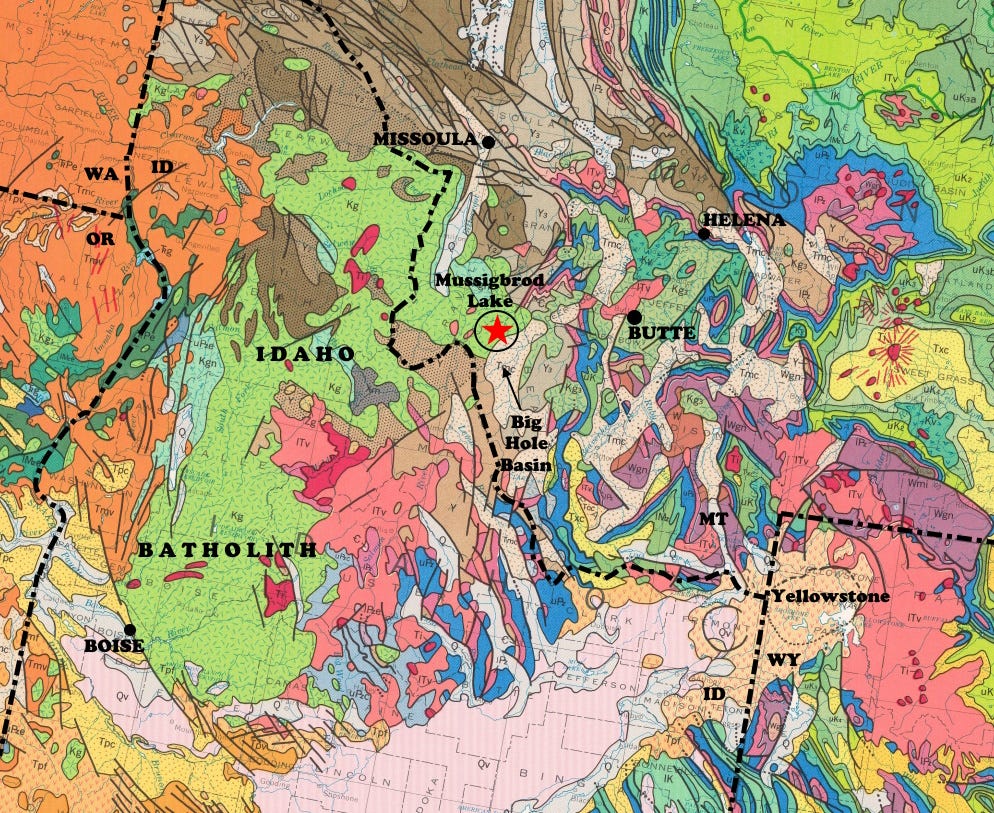

This spectacular outcrop, one of the most intriguing I’ve ever seen (and I’m both old and have been around), is about 29 km (18 miles) up a Forest Service road, then about 3 more kilometers by trail. It’s above Mussigbrod Lake, near the intersection of the Anaconda Range and Beaverhead Mountains, west of the upper Big Hole River in far southwestern Montana USA.

A migmatite (from Greek words for a mixture and rock) is a rock metamorphosed at some position where it was hot enough that some partial melting occurred. That could be at relatively great depth, or relatively close to a hot igneous body. Either way, the migmatite in these photos is a composite of metamorphic and igneous material. The big (10 to 100 cm and more) somewhat rounded darker blocks are essentially xenoliths (“strange rock”) of foliated (layered) metamorphic gneiss that are incorporated into the formerly molten igneous portion that may have derived from partial melting of the original parent rock. The granitic igneous material is the more vein-like, lighter rock that cuts across and surrounds the darker, layered metamorphic rocks in these photos.

I think the present thinking is that this represents contact metamorphism, but on a regional scale, associated with elements of the Idaho Batholith. Are the igneous portions simply small branches of the granitic batholith’s formerly molten material? Or are they material that truly did form by re-melting of pre-existing material, either the batholith, or the country rock, or both? The answer is probably “all of the above,” but details may lie in geochemical analyses and further mapping. The current best estimate for the age of the igneous material is around 70 million years, consistent with something associated with the Idaho Batholith.

This area is mostly mapped at present as late Cretaceous and early Tertiary granitic rocks, but most of the metamorphic xenoliths are probably intensely metamorphosed Belt Supergroup sedimentary rocks (biotite gneiss and other rocks) originally deposited about 1,400 million years ago. Some might be metamorphosed granitic rocks (granite gneiss, granodiorite gneiss) of the Idaho Batholith that had solidified earlier, only to be metamorphosed by a later phase of the intrusion (mostly around 76 to 63 million years old).

The rocks are part of a large area that is probably in the footwall (lower block) of a fault zone that looks like it is a southwesterly continuation of the Anaconda Detachment, a zone along which a huge mass of rock slipped (not really like a landslide, but in the subsurface) to the east off a high-standing block.

Equivalent rocks are found in the hanging wall (upper block) of the detachment fault zone to the east, indicating that the fault sliced through the older rock package. In a simpler context, the area around Mussigbrod Lake would be called the metamorphic core complex, the uplifted, metamorphic core that produced the gravity gradient that led to the detachment faulting, but here the rocks are millions of years older than the detachment, which is perhaps as old as 50 million and as young as 25 million years. So it’s not a metamorphic core complex in the commonly accepted sense of the term.

The present high-standing mountains where Mussigbrod Lake lies are the southwestern extension of the Anaconda Range. Their uplift has been enhanced by relatively recent faulting that dropped the basin of the upper Big Hole River down significantly relative to the present mountains. That basin lies east and southeast of Mussigbrod, around Wisdom, Montana, and probably contains at least 4900 meters (16,000 feet) of post-uplift (Tertiary, probably younger than about 40 million years) sediment fill (Hanneman and Nichols, 1981, Late Tertiary sedimentary rocks of the Big Hole basin, southwest Montana: Geological Society of America (Rocky Mountain Section), Abstracts with Programs, vol. 13, no. 4, p. 199).

Colleen Elliott provided insights and information that improved this post, but she is not responsible for my mistakes and delusions. Colleen will be leading a field trip to this area during the 50th Annual Field Conference of The Tobacco Root Geological Society in July 2025.

In 2000, 85,000 acres burned around Mussigbrod Lake. I was living at the Indiana University Geologic Field Station at the time, about 125 km (80 miles) downwind, and I remember well the rain of ash, including entire ashed pine needles, that fell there. The fire had a small benefit of making this outcrop a little more evident. My photos are from 2016.

Mussigbrod Lake was a small natural glacial lake and lowland, enhanced by a circa 1925 dam and a higher 1969 dam, both built to provide irrigation water to the Big Hole Valley.

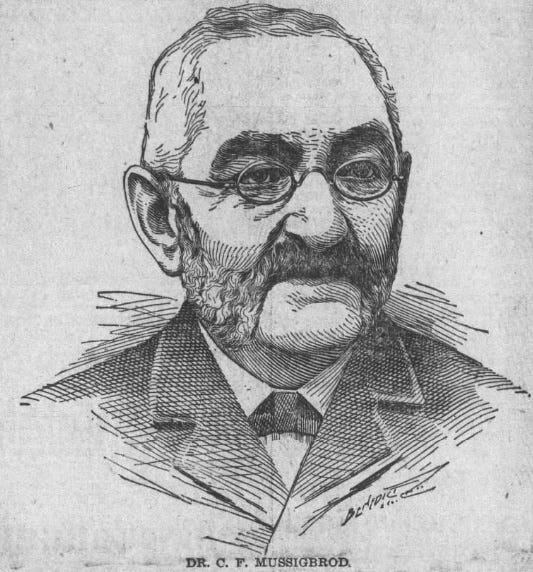

Charles F. Mussigbrod was a pioneer miner and physician, born to a German family near St. Petersburg, Russia, in 1815, and who grew up in Germany. He came to southwest Montana in the Bannack gold rush of 1863, and started the asylum at Warm Springs beginning in 1877. Dr. Mussigbrod was an officer of the Lotus social club in Butte and was one of the initially appointed city commissioners of Butte in 1879. He was an early investor in mines at Garnet where his son Peter eventually became a manager. Charles died in Berlin, Germany, in 1896, where he had gone to seek medical attention.

Thank you, Richard. Once again your clear writing makes a technical subject understandable to the layman.

Loved this! In my much younger days, camped and fished at that lake! Trees then so dense it was like a jungle.

Now I know some of the geology, it’s a more precious memory.